Private banks are tightening their belts. Many smaller wealth managers are questioning the bottom-line value of bulking up digitally, Synpulse innovation head Frank Troise writes in an exclusive essay for finews.asia.

Cost cuts are front and center for finance chiefs and operating heads at private banks, which are preoccupied with improving their cost-income ratio.

The financial measure is coming into closer focus as competition among wealth managers heats up. It is also key for investors to gauge how efficiently private banks are offsetting their revenue and spending: if the ratio rises from quarter to quarter, executives are quickly taken to task.

What about investing in bespoke digital initiatives to win a new generation of wealthy clients?

«Cost-income ratios meet robo-adviser reality»

For now, Asian wealth managers compare favorably in a Standard & Poor’s compilation of average cost-income ratios worldwide.

Of late, the key cost-income ratio we have heard cited most often from financial service finance chiefs is 65 percent. I will not debate the merits of this specific ratio, but will instead use it the same way as a Chief Financial Officer (CFO) would, when considering any internal finTech initiative.

The consequence of a specific cost-income ratio target is that it makes it quite easy for a CFO to determine the reality of breaking even after implementing a fintech initiative such as setting up a robo-adviser.

«Costs surge to an unsustainable level in private banking»

For example, a $100 million wealth management business levying 1.5 percent for investment fees will make $1,500,000 every year. At a cost-income ratio of 65 percent, our costs would total $975,000. In other words, $975,000 divided by $1,500,000 equals 65 percent.

Let’s say our CFO now opts to build a robo-adviser. For ease of calculation, let’s assume a $500,000 "fee" to implement the robo-adviser on a bespoke basis.

This additional expense immediately disrupts our CFO's CIR model: the ratio has now surge to 98.3 percent from 65 percent, a level unsustainable for the business. The math: $1,475,000 divided by $1,500,000.

«Win considerable new business, or slash spending»

So what should our CFO do? His or her option is to grow his way out by acquiring new assets and winning more fee income. His other option is to slash spending.

In our model then, the CFO would need to grow fee income by $769,230 to reclaim his cost-income ratio of 65 percent, or reduce 100 percent of his headcount. Both options are extreme, and we can surmise that our CFO would most likely blend approaches to maintain the cost-income ratio.

«Cost-income ratios dictate assets required»

The subtler theme emerging is that cost-income ratios are dictating assets and management fees required for a successful robo-advisor launch, and/or the actual cost of robo-adviser integration.

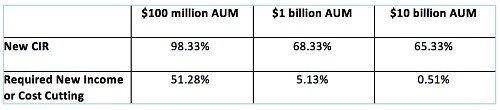

In the table below, we have extended the analysis to several scenarios:

The smallest wealth manager, with roughly $100 million in assets, would need to offset the surge in spending with a more than 50 percent rise in revenue – or lower costs by that measure, for example by cutting jobs.

For the largest with at least $10 billion in assets, the cost-income rise is negligible: this advisor can afford to splash out $500,000 on building a bespoke robo-adviser solution.

«Bespoke robo-adviser is not feasible with less than $100 million»

The bottom line is that for advisers with less than $100 million in assets, a bespoke robo-adviser is not feasible. Why not seriously consider using a free business-to-business (B2B) solution? These typically include a share of revenue for the back-end provider.

The subtlety is not lost on wealth managers: the robo-adviser’s value proposition is «low fees». If advisers were to drop gross fees by 100 basis points to 0.5 percent, their cost-income ratio would slide. It also lends itself to fee cannibalization from prior, more profitable legacy business.

Advisers need to think about the value of digital wealth solutions in light of lower fees, a tougher client acquisition process, and a hit to costs.

Frank Troise is head of innovation at Synpulse, a financial services consultancy. He began his career as a management consultant with stints in proprietary trading, risk management and private banking in Los Angeles, CA. He founded Soho Capital in 1997, which he sold in 2015.