Credit Suisse: Time for a Change

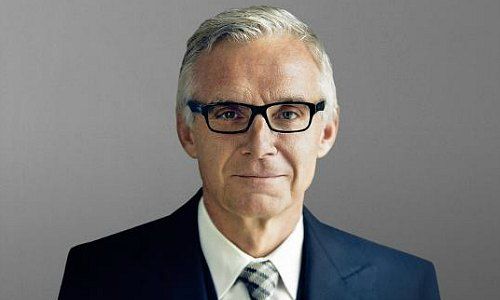

Credit Suisse’s mortgage settlement in the U.S. presents an opportunity for chairman Urs Rohner to retreat. The Swiss bank has scant chance of retrenching under his leadership.

Calls from finance circles for Urs Rohner to step down as chairman of Credit Suisse’s board aren't new: he first faced them in 2013, when the bank paid an eye-watering $2.5 billion to U.S. officials for helping Americans cheat on their taxes.

It was one of several several strategic missteps by the bank in recent years which have cost shareholders dearly. Secondly, Credit Suisse has been pitifully capitalized, even sparking a rare public rebuke from Switzerland’s central bank in 2012. And thirdly, the bank’s numerous fines and penalties are impeding its ability to make a credible fresh start.

Miserable Record

Thus it is hardly surprising that the board – under Rohner’s leadership – is widely considered to be at fault. Even if the individual members have impressive qualities, as a body they have failed.

Rohner’s earlier refusals to step down – in 2013, for example, when he was under pressure as former general counsel after the bank pled guilty in the tax probe – could be explained with the desire to clean up Credit Suisse and help resolve its problems.

Three years on, and with Credit Suisse facing one of the biggest fines in its history, the time for a change at the top of the bank’s board is ripe. Investors may be buying Credit Suisse stock in a short-term relief rally over the most recent U.S. settlement, but the bank’s mid- and long-term prospects are dim.

Seven arguments underpin this view:

1. Board Failure

The bank’s board has been heavily criticized for at least two years: first for squandering its advantage coming out of the financial crisis, later for an almost lethargic approach to increasingly big problems of both strategic nature as well as personnel.

The body has shown no leadership: the board largely kept mum even when Tidjane Thiam came under pressure as Chief Executive – few decisive statements or public backing were heard.

The board has also failed to make any noteworthy staff changes. The U.S. mortgage disputes resolution provides a perfect opportunity for Rohner to clear the way for new presidential leadership.

2. Compliance Eats Millions

Factoring in costs related to the U.S. settlement, spending for litigation has skyrocketed to roughly 10 billion Swiss francs in recent years. At the same time, the bank has massively ramped up its compliance department by millions of Swiss francs – not least as a result of various missteps and wrong-doing.

Thus, the bank’s behavior results in a spending double-whammy, be it in offshore dealings with well-to-do Americans, subprime mortgages, or dark pool dealings. It is cold comfort to Credit Suisse’s shareholders that the entire finance industry shoulders the same compliance financial burden as Credit Suisse does.

3. Feeble Capital Hits Shares

Short-term worries about Credit Suisse may have disappeared, but the fact remains that this settlement – and others pending – are a massive blow to the bank’s capital strength.

Questions over Credit Suisse’s capital position will linger, and spill over into the performance of the stock. The bank’s shares aren’t a smart long-term investment against this backdrop.

4. Impact on Swiss Unit

The most recent fine will push Credit Suisse’s Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio back down to the 11 percent mark under Basel III rules. The question is, what does that mean for the Swiss unit, and its planned IPO next year in particular?

Credit Suisse says that a carved-out Credit Suisse Switzerland will need more capital than the Swiss universal bank structure which preceded it. This would hit the unit’s return on equity and ultimately its valuation.

In short: Credit Suisse may reap less out of the listing than it had hoped, which means it won’t get the capital relief the parent company desperately needs.

5. Payment Method Counts

The fine for mis-selling mortgage securities will be an albatross around Credit Suisse’s neck for the next five years: that’s how long the bank is required to provide so-called consumer relief to damaged parties, and it translates to an average of $560 million per year.

It’s unclear how the payments are to be staggered; the effect of the long-dated payments on Credit Suisse’s results and capital situation can more reliably be judged when this information is made public.

6. Another Loss-Making Year

If investors had hoped that Thiam’s kitchen-sinking was over with a 2.9 billion franc last year, they face a loss-making 2016 too. Vontobel analyst Andreas Venditti puts the bank's full-year net loss at more than 1 billion francs.

This puts pressure on the bank’s ability to make a payout to shareholders. Last year, Credit Suisse paid out 0.70 francs despite the loss, but it is questionable whether the bank can pull off a similar feat this year given its weak results and feeble capital position.

7. Demise of Business Model

Comparing the business models of Switzerland’s two largest banks in the last ten years, there has almost never been a period of stability. Both firms have suffered major setbacks, most of which they withstood thanks to their size alone.

Instead of allowing shareholders to participate in their successes, bank bosses have made headlines with huge paychecks while paying lip service to moderation in pay schemes.

More grievously, enormous potential conflicts of interest arose between the business units of universal bank: private bankers and investment bankers may play nice on paper and generate synergies. In reality however, the two are far from this idyll, save for a few isolated instances.

A universal bank has never made much sense for shareholders: the individual units’ risk tolerance are so dramatically different that it is difficult for a shareholder to track in what exactly he or she has invested in.

Add a retail client business to the mix and the chaos is complete. This is one reason that both UBS and Credit Suisse, each in their own way, have hived off this unit – a clear indication that the demise of the universal bank is nigh. The disruptive power of fintech and other upstarts will also extract a toll, with clients tending to many routine aspects on finance themselves and outside of traditional banks.