Not only due to its geographical location, IWC in Schaffhausen stands out among Swiss luxury watch manufacturers. From the beginning, the company has been characterized by its forward-driving technological ambition. In 1985, it became world-famous for a special invention. A visit to understand its legacy.

When you walk from the old town of Schaffhausen to the IWC company premises today, the path leads through an urban area. The slightly winding headquarters, which shows its multiple construction phases, exudes industrial charm right in the middle of the city.

It wasn't always like this. Founded as the International Watch Company in 1868, IWC's main building was largely standalone when completed in 1874, directly connected to a hydroelectric power plant on the Rhine, which provided the energy to drive the machines.

American Roots

At the beginning of the IWC story stands the industrial ambition of an American: Florentine Ariosto Jones (1841-1916) had traveled to Switzerland to look for cost-effective opportunities to manufacture movements for pocket watches, which were very popular in America at the time. Switzerland was considered a low-wage country.

He also visited the Jura, the then and now heart of the watchmaking industry. However, the mentality of the watchmakers there—many of whom worked in small workshops or even from home—seemed too backward to him to build a pioneering industrial company with modern manufacturing techniques.

Largely detached at the beginning: IWC's main building in the 1870s. (Image: IWC, courtesy)

So, Schaffhausen. In the early years, IWC exclusively produced movements for the American market. The watches were then married with cases and branded, for example, in New York.

Turbulent Early Years

However, the business venture proved to be difficult. There were several bankruptcies and changes in ownership until IWC found a buyer in Johannes Rauschenbach (1815-1881), an industrialist from Schaffhausen. He paid 260,000 Swiss francs ($292,000), half of the estimated value.

Afterwards, the company remained in the hands of the Rauschenbach and, through marriage, Homberger families for nearly 100 years. For some time, the physician and founder of psychoanalysis, Carl Gustav Jung (1865-1971), was also a shareholder. In 1902, he married Emma Rauschenbach (1882–1955), the daughter of the buyer and savior of IWC

This is the current collection of the Portugieser model. (Image: IWC, courtesy)

During this long period shaped by the families, all of the five current model lines were launched: The Pilot's watches from 1936, which IWC supplied to, among others, the German Luftwaffe and the Royal Air Force; the Ingenieur model series, the world's first antimagnetic watch for civilian use (first produced in 1955 and redesigned by Swiss artist and watchmaker Gérard Genta in 1976); the Aquatimer diver's watches from 1969; the DaVinci line from 1969 onwards; and of course, the legendary Portugieser, named after being initially produced in the 1930s for two watch dealers from Portugal.

Public Museum

The rich history of models can be experienced at the IWC Museum, also located at the headquarters in Schaffhausen and open to the public. This attraction reportedly enjoys great popularity among tourists. From the earliest pocket watches to epoch-making model creations and evolutions, nearly all significant models ever produced by IWC are exhibited here.

Recently, as a loan, the original pocket watch gifted to English Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965) just before the end of World War II is also on display here.

94 Registers

In 94 thick registers, meticulous records are kept of every watch ever produced and their buyers up until the 1970s. Since then, recording was initially done on index cards and later electronically. IWC refers to this historical repository when issuing certificates of authenticity. The service department can still service or repair any mechanical watch that has left the workshop since the early days.

The watch crisis of the 1970s due to the Quartz boom severely affected IWC. The number of employees in the Swiss watch industry decreased by two-thirds. In 1978, the Rauschenbach and Homberger families sold the company to the German automotive supplier VDO.

Epochal Invention

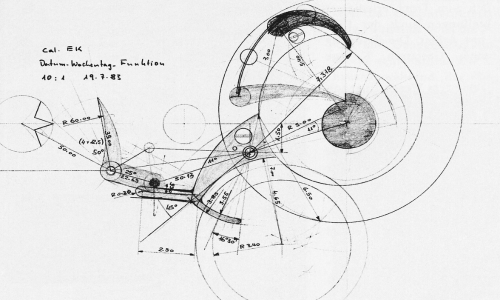

Under VDO's leadership, IWC doubled its efforts in technology and mechanics against the Quartz trend. This effort paid off: In 1985, Swiss watchmaker Kurt Klaus, born in 1934, invented the crown-operated Perpetual Calendar for wristwatches at IWC—since then considered the pinnacle of mechanical watchmaking in complications. It accurately accounts for leap years and irregularities in the frequence of leap years.

In its latest generation, IWC's Perpetual Calendar promises a moon phase display accurate to 45 million years. It not only recognizes different month lengths and adds a leap day at the end of February every four years but also automatically adjusts for the complex exception rules of the Gregorian calendar, where a leap year is skipped three times over a 400-year period.

A few weeks ago, the IWC Portugieser Perpetual Calendar was included in the Guinness Book of Records as the most precise wristwatch with moon phase.

Technical sketch of the Perpetual Calendar by Kurt Klaus, 1985. (Image: IWC, courtesy)

Since the invention of the Perpetual Calendar, IWC has occupied a special place in the hearts of mechanical watch enthusiasts. The industrial pioneering spirit is palpable when touring the Schaffhausen premises to this day: Everything appears as clean and organized as in a scientific laboratory, with processes meticulously planned and executed.

While IWC does order individual components from suppliers, the motto remains: Where things truly become complex and demanding, they do it themselves. Currently, IWC models feature no fewer than seven different in-house movements, including the Calibre 52 with a world-record-breaking power reserve of seven days.

Since 2000 at Richemont

After VDO's acquisition by Mannesmann in 1994, IWC, along with other prestigious brands Jaeger-LeCoultre and A. Lange & Söhne, was consolidated under the holding Les Manufactures Horlogères.

In 2000, Richemont, the Swiss luxury goods conglomerate founded by Johann Rupert, acquired the trio of watch brands from Mannesmann for 3.5 billion Deutsche Marks, or 1.8 billion Euros. The company was successively led by Georges Kern (2001 to 2017) and Christoph Grainger-Herr (since 2017).

Hardly Affected by Downturns

Since then, the Schaffhausen watch factory has further expanded significantly. Part of the secret to its success is the high level of autonomy granted to IWC within the conglomerate. In terms of technology and design, IWC operates almost entirely independently from the group, with no pressure to standardize or seek synergies.

Due to space constraints at its headquarters, IWC opened a new manufacturing center six years ago outside the city center. Inspired design-wise by star architect Mies van der Rohe, it accommodates an additional 400 watchmakers.

New IWC Manufacturing Center in Schaffhausen. (Image: IWC, courtesy)

IWC has also been making creative strides in marketing for years. This includes Formula 1 engagements (as reported by finews.ch) and collaborations with brand ambassadors such as Gisele Bündchen, Lewis Hamilton, and Hans Zimmer.

The combination of technological leadership and top-tier luxury goods marketing appears to be successful even in challenging times. According to industry experts, IWC is hardly affected by the current downturn in demand for luxury watches. However, one ingredients of the brand's success is also that it never communicates any numbers.