Stefan Gerlach: «How Does the Fed Expect Interest Rates to Evolve?»

The Federal Reserve has repeatedly overestimated the strength of the U.S. economy, Stefan Gerlach writes in his essay for finews.first.

finews.first is a forum for renowned authors specialized on economic and financial topics. The texts are published in both German and English. The contributions appear in cooperation with Pictet, the Geneva-based private bank. The publishers of finews.ch are responsible for the selection.

How much and how quickly the Federal Reserve (Fed) will raise interest rates will matter hugely for the global economy. This blog post analyses the Federal Reserve’s public statements and shows how its expectations of the path of U.S. monetary policy has had to change as it has repeatedly overestimated the strength of the U.S. economy.

It also shows how the Federal Reserve’s assessment of the longer run level of the federal funds rate has declined by about 100 basis points over the last few years.

Since a rapid tightening of U.S. monetary policy risks appreciating the dollar, and depressing equity and bond prices in the U.S. and elsewhere, market participants naturally seek to form a view of how U.S. interest rates may evolve. One source of information is speeches of Fed officials. Unfortunately, it is not always clear how these should be interpreted. Another source of information is the quarterly «dot plots» which contain the views of the members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) regarding what interest rates they believe are needed for the Fed to achieve its targets.

«Nevertheless, it is useful to have a sense of the Fed’s thinking»

The information in the dot plots apply to the end of the current and next two years, and in «the longer run». One can use these plots to estimate the full path of federal funds rates that FOMC members, on average, think will be appropriate. Of course, there is no reason for interest rates to actually evolve this way as the FOMC may find that it has misjudged economic and financial conditions. Nevertheless, it is useful to have a sense of the Fed’s thinking.

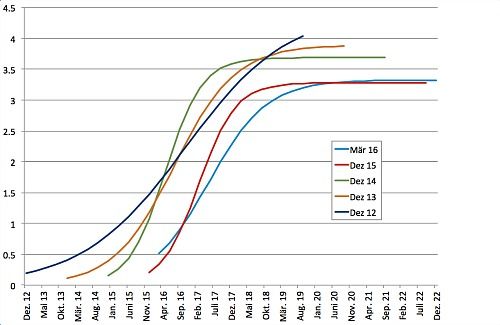

The figure shows the results of this analysis for the FOMC’s meetings in December 2012, December 2013, December 2014, December 2015 and for March 2015. The findings are striking.

In December 2012, the Fed thought that interest rates would reach 50 basis points around 9 quarters later. They would then rise rapidly and reach just above 4 percent in seven years, which is the assumed «longer run» in this analysis, and rise a little bit further before levelling off around 4.25 percent. That corresponds surprisingly well with the pre-crisis view that with an inflation objective of 2 percent, the federal funds rate should average about 4 percent.

«The situation had changed markedly»

By December 2013, after the «taper tantrum» in May 2013 when Chairman Ben Bernanke first raised the idea of tapering the rate of expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet, the situation had changed markedly. FOMC members then felt it appropriate for rates to rise more rapidly than a year earlier and to plateau a little below 4 percent, that is, lower than before.

In December 2014, FOMC members anticipated more rapid interest rate increases than before. Furthermore, they thought it likely that the Federal Funds rate would level off a little above 3.5 percent, that is, about 0.5 percent below the level they anticipated two years earlier.

In December 2015, when the FOMC finally raised interest rates, members felt that very much the same interest rate trajectory as a year earlier would be appropriate, except that interest rate increases had been delayed by about four quarters. They were also expected to end earlier than before, at just below 3.5 percent.

Finally, in March 2016, following the financial markets turmoil in the first quarter, the FOMC believed that interest rates should be increased more gradually than in December 2015. It also viewed it appropriate for the federal fund rate again to plateau at a similar level to in December, at about 3.3 percent.

«This suggests that future returns in the U.S. bond market will be much lower»

What useful information can be drawn from these curves? First, the graph shows how the FOMC misjudged economic conditions and repeatedly had to delay tightening policy. While that has been much commented on in the newspapers, the Fed continues to believe that it will have to raise rates very rapidly. For instance, by the end of next year it expects the federal funds rate to be about 2.25 percent. That seems implausible. Further delays can be expected.

Second, the graph shows how the FOMC’s assessment about the longer run level of interest rates declined by almost 1 percent between 2012 and 2016. This suggests that future returns in the U.S. bond market will be much lower than the historical record indicates. It is clear that the Fed sees U.S. monetary policy after normalisation as very different from what came before.

Stefan Gerlach, a dual Swedish-Swiss citizen, has been the Chief Economist at BSI Bank since the beginning of this year. Previously he worked for four years as one of two Deputy Governors of the Bank of Ireland and before that at the Bank for International Settlements and as Chief Economist with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority.

Previous contributions: Rudi Bogni, Adriano B. Lucatelli, Peter Kurer (twice), Oliver Berger, Rolf Banz, Dieter Ruloff, Samuel Gerber, Werner Vogt, Claude Baumann, Walter Wittmann, Albert Steck, Alfred Mettler, Peter Hody, Robert Holzach, Thorsten Polleit, Craig Murray, David Zollinger, Arthur Bolliger and Beat Kappeler and Chris Rowe.