The Cities Breathing Down London's Neck

The City of London is quivering at the prospect at losing as many as 70,000 banking jobs as a result of Britain's vote to leave the European Union. The reality is that London has already lost hundreds of jobs.

Dublin: Nearest Neighbor

Britain may have voted to leave the European Union, but the Republic of Ireland is still part of the bloc. Its proximity to London makes Ireland a natural choice for international finance firms who have until now used London as a «passport» for the EU. A common language, intact infrastructure and lower salary costs than in the City will make Dublin an appealing alternative.

The exodus from London to Dublin had already begun well before the Brexit referendum ramped up: Credit Suisse (CS) moved part of its investment bank to Ireland in 2015. In January, the Swiss bank opened a trading floor in Dublin (picture above) which will house roughly 100 CS traders.

Further shifts towards Dublin are expected to follow as banks eye up major staff shifts following the Brexit vote. J.P. Morgan has threatened to move about 4,000 jobs out of the U.K., while Citigroup has already decided to shift the back office for its retail bank to Dublin, according to the «The Telegraph».

Ireland, currently the second-largest funds center in Europe, could also be up for grabbing a piece of Britain's fund management cake. Ireland's aggressive marketing of itself as a financial center is legendary – Irish delegations have even visited Switzerland in the hope of drumming up business.

Paris: The Investment Bankers' Choice

President François Hollande has shown that he is willing to let London bleed following Brexit. He has griped that it is «unacceptable» that euro trading remains in London. This can be interpreted as a hint to other financial centers and a simultaneous marketing ploy for France.

The fact is that Paris stands an excellent chance of grabbing investment banking share off London. The French capital (above, picture Shutterstock) is not only part of the block, it is also a city of sophistication and culture – and a finance hub with a rich history.

Investment bankers are likely to prefer this option. HSBC has already considered moving some 1,000 jobs to the city on the Seine.

However, it is questionable whether Paris can spark a trend: France is politically and economically less stable. Extremely high costs for labor and commercial real estate – as well as Europe's most restrictive labor laws.

Frankfurt: Big Bonuses

«Mainhattan» has also mounted an appeal to win business off London following Brexit. Local promoter Frankfurt Main Finance has calculated that about 1,000 jobs, particularly in euro derivatives trading, clearing and settling of trades, will move to Frankfurt (above, picture from Shutterstock) in coming months, according to «Sueddeutsche Zeitung». Lobbyists expect more than 10,000 jobs to move to Frankfurt in total.

J.P. Morgan and Morgan Stanley have denied rumors that they plan a major shift of jobs to Frankfurt. The city's appeal is the proximity to the European Central Bank, excellent transportation infrastructure – and an exchange point which is responsible for about 40 percent of Europe's Internet traffic.

One further, powerful incentive for bankers to move to Frankfurt is money. While salaries are generally lower than in London, this is offset by a far lower cost of living.

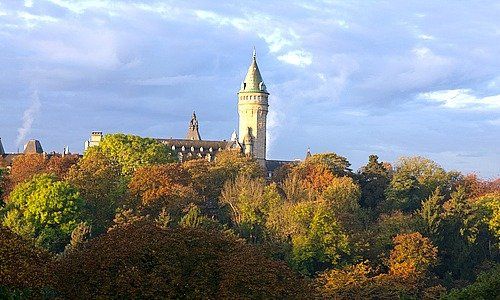

Luxembourg: Nimble Heavyweight

Luxembourg may also be a candidate to inherit some of London's bankers – it is already a funds center for Europe thanks to taxation which is friendly to institutional and retail funds. The grand duchy has also reportedly been eyed as an alternative to London by J.P. Morgan and HSBC before the Brexit vote. Both banks already have offices in Luxembourg (above, picture from Shutterstock).

According to Europe's investment management industry group, EFAMFA, the grand duchy already manages roughly half of the 8 trillion euro fund management industry. It is eminently possible that Luxembourg manages to grab some of the 13 percent currently managed in Britain.

Thanks to a pragmatic and agile approach to regulation and taxes, Luxembourg's finance center has secured itself back-office and fintech business – a basis it can build on. It is also expected to benefit from Brexit in areas such as Islamic finance.

Switzerland: Burned Bridges

The alpine nation already kissed a good part of the finance industry goodbye after introducing a stamp duty in the 1990s. The finance industry's long memory will make it hard for Zurich or Geneva to attract big parts of investment banking from London. More importantly, Switzerland still doesn't have unfettered market access to the Eurozone – big banks have used offices in London or Germany as «passports» for an entry into Europe.

By contrast, Switzerland has proven a popular destination for specialized asset managers. Schroders ramped up production in Switzerland, and prominent hedge funds like Brevan Howard or Leda Braga operate out of Geneva in addition to London.

To be sure, Switzerland has to sharpen its profile should it want to attract more asset managers from Europe – or fintech players, which have until now clustered in London.

Wroclaw, Bratislava, Budapest: Further Afield

The banks have also quietly been moving thousands of jobs to less expensive cities in the Eurozone – both in and out of the U.K. – as an increasingly electronically conducted business doesn't require traders and support staff to be in the same place.

London's high costs and skyrocketing property market have prompted many banks to move staff that don't necessarily need to be in London, but in the Eurozone. It is the lesser-known and unglamorous side of investment banking, such as clearing, settling, or treasury services for corporate clients.

For example, J.P. Morgan employs some 4,000 people in Bournemouth, while Deutsche Bank has approximately 2,000 people in Birmingham.

A host of banks including Morgan Stanley, RBS and Barclays have moved staff in recent years to Glasgow, where salaries are far lower than in London. J.P. Morgan is setting up a tech center in Scotland's largest city, cutting support roles in Switzerland due to the strong Swiss franc and from India, where it is increasingly difficult to find highly skilled support staff after an influx of foreign firms.

Financial firms including UBS and Credit Suisse have spent millions in recent years on so-called near-shoring efforts, ramping up on back-office staff in Eastern European cities like Wroclaw (pictured above) and Krakow in Poland, Budapest in Hungary or Bratislava in Slovakia.

These areas could benefit if banks decide to abandon operations in cities such as Bournemouth or Birmingham in favor of cities in the bloc.