The disaster pile-up by Credit Suisse causing billions in losses leads to a single conclusion: the Swiss bank needs a major strategy overhaul under new oversight.

The situation at Credit Suisse is precarious: board, management, and crisis committees are scrambling to deal with twin catastrophes. As they sift through potential financial wreckage in the billions and look for causes, correlations, effects, and accountability, the Swiss bank is trying to calm investors, regulators, and not least its own employees.

Credit Suisse doesn't have an estimate of the damage yet – nor is it ring-fenced. The Greensill debacle, which blew up in the bank's face three weeks ago, is a slap in the face for clients in asset management and private banking.

The botched handling of margin calls on prime brokerage client Archegos raises questions over the bank's investment banking acumen. Its obviously overloaded risk management is an issue for regulators and ratings agencies alike.

C-Suite Changes Ineffectual

The sum total is a major whack to Credit Suisse's reputation, which can lead to fund withdrawals and kneecap its ability to win new clients, frustrate employees in other, better-functioning areas of the bank, and imperil its chances of attracting top talent.

The circus on Paradeplatz won't be able to smooth over 12 months of missteps including Luckin Coffee, Wirecard, Softbank, York Capital, and now Greensill as well as Archegos – by switching in a new CEO or other top executives, or by making some changes at its investment bank or in its risk management.

Depleted Capital Levels

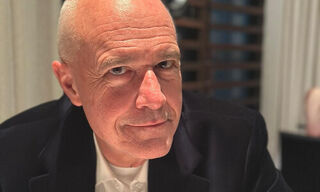

To take the popular business-school saying, the fish rots from the head down. If so, the departure of long-standing Chairman Urs Rohner in four weeks is a start. The 61-year-old's legacy is that of a lost decade for once-proud Credit Suisse.

The bank's strategy was already outdated under ex-CEO Brady Dougan after the financial crisis of 2008/09, but Rohner and a rather disparate group of directors assembled by the Swiss trial lawyer left the American CEO to his devices, even after Swiss regulators stepped in to intervene due to depleted capital levels.

Master Strategist Tidjane Thiam?

Tidjane Thiam, feted by «Euromoney» as a master strategist, did little more than carve up a new division structure, slash spending, and pare back an oversized investment bank. The French-Ivorian CEO did manage to squeeze a badly-needed 10 billion Swiss francs ($10.6 billion) of capital out of shareholders, in two separate cash calls within just 18 months.

However, Thiam's orchestration of Credit Suisse as «a leading private bank and wealth manager with strong investment banking capabilities» as outlined in 2015 has failed.

The result of ten years of Rohner presiding Credit Suisse (in which he pulled down more than 34 million francs) and five years after an apparent change in strategy is sobering: the stock is 70 percent lower than in 2011. Rohner's 2018 pledge, after a scrape with major institutional shareholders the year before, to pay cash dividends after years of scrips, is proving a damp squib.

Specter Of Capital Increase

Analysts expect Credit Suisse will halt its 1.5 billion franc share buyback. The cumulative billions from the bank's involvement with Greensill and Archegos jeopardize shareholder payouts this year. The Swiss lender's capital looks in danger of falling below 12.5 percent – the specter of another cap hike looms.

António Horta-Osório, the Lloyds boss who takes over from Rohner on April 29, may have expected to confront a restructuring case, but in fact, he must reinvent the bank from top to bottom.

Lightweight And Subscale

The most recent problems illustrate that Credit Suisse's current strategy doesn't add value: Greensill and its boss Lex Greensill illustrate the limitations of the lofty «one-bank» idea for some major clients to draw tailored investment banking expertise alongside their wealth management advice.

Credit Suisse's investment bank alone is too lightweight to compete with Wall Street giants, and its wealth and asset management arms are subscale to compete with larger industry players.

The bank needs a fundamental transformation as well as a cultural change to maintain its relevance given the rapid advances of technology in finance in coming years, as Rupak Ghose (a former Credit Suisse equity research analyst) wrote for finews.com this week.

It is difficult to conceive Credit Suisse's major shareholders – which include Natixis-owned Harris Associates, Qatar's sovereign wealth fund, and the wealthy Olayan clan – won't finally insist on a radical change in strategy.

Where Added Value?

Horta-Osório's biggest problem is that Credit Suisse simply doesn't have the resources to compete in a technology-based arms race that U.S. banks are driving. This critical limitation will inevitably lead Credit Suisse to strategically focus on fewer business areas – and likely to some disposals.

The troubled asset management unit is already in train, the other divisions starting with capital markets will follow shortly. In the cold light of day, Horta-Osório and big shareholders may find that splitting up Credit Suisse's domestic unit may bring the added value that shareholders have futility been looking for until now.