In nearly a decade at UBS, Sergio Ermotti went from a trader’s calculated gambles to an extreme reluctance to take risks. finews.asia on the Swiss banker’s near-total reversal.

When Sergio Ermotti became CEO of UBS in 2011, he wasn’t genuinely given the job and he wasn’t even UBS’ first choice: rocked by a $2 billion rogue trading scandal, the Swiss bank had a leadership vacuum to fill.

Ulrich Koerner, then operating chief of UBS, was the board’s first call – but he wasn't willing to add «interim» to his title and made a play to take the job outright. By contrast, Ermotti, who had joined the Swiss bank from Unicredit just one year before, acquiesced to UBS’ request to stand in temporarily during a search process for a new CEO.

It was a fateful gamble for the Swiss banker: he endured an eight-week search before UBS formally made him CEO, in November 2011. Ermotti, who had made it within striking distance to replace Alessandro Profumo at Unicredit before being passed over in 2010, had learned to sweat it out.

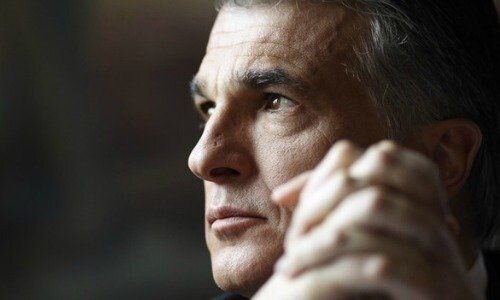

(Sergio Ermotti, at left, and Kaspar Villiger, UBS chairman in 2011; Image: Keystone)

Apple of Finance

It is easy to forget that UBS, which now pays a «boredom premium,» was in disarray when Ermotti arrived: he was the fourth CEO is five frantic crisis years. It was mired in every scandal, from rigging benchmark interest rates to colluding in precious metals markets.

Ermotti, a native of Ticino, was on a mission: he saw UBS as an Apple or IBM of the financial industry, he repeatedly said in interviews. Less than a year later, he unveiled a transformation of UBS: as many as 10,000 employees would be let go in a dramatic bloodletting at its investment bank.

This second decisive tactical gamble from Ermotti had all the hallmarks of his dealing room past: ballsy, shrewd, and all-in. «Change is necessary for the entire banking industry,» he wrote in a memo to staff at the time.

Mocked, Then Applauded

The transformation came against the backdrop of a new Chairman, Axel Weber. Ermotti wasn’t the ex-Bundesbanker’s first choice, it later emerged, but the CEO was in the job six months before Weber was formally allowed to take over on the board.

The duo quickly overcame any unease and set about the three-year plan, which included juicier shareholder payouts. By 2014, the duo, who had initially been mocked in some quarters for the dramatic 2012 plan, was able to take a victory lap.

UBS was named the best global bank in a widely-watched annual «Euromoney» evaluation that year. In 2015, it hit one of its targets: paying out more than half of its profits to shareholders (its payout ratio that year was 52 percent).

Rivals «Do a UBS»

Ermotti feted the narrow spread of credit default swaps on UBS – CDSs reflect the cost of default protection – compared to U.S. peers like J.P. Morgan. It was a telling sign of what was to come later.

Rivals like Credit Suisse began to «do a UBS,» imitating the wealth push while downgrading their capital markets arms. Meanwhile, UBS was roiled by what Ermotti would later call a «perfect storm»: Switzerland’s central bank in 2015 ended its cap on the franc against the euro, sending the Swiss currency surging.

UBS' flagship wealth management arm, then led by Juerg Zeltner, was hit hard by the «Frankenschock» and China's booming economy showed signs of slowing down. By 2016, UBS was forced to tweak its landmark strategy account for negative interest rates and what Ermotti called the utter unpredictability of central banks, dropping some of its financial targets in the process.

«Paranoid About Risk»

The following year, UBS’s conservatism became apparent: its private bank was reluctant to use a balance sheet to lend to billionaires, a common practice among wealth managers to hike assets. UBS didn’t necessarily want those either, though – at least not franc-based deposits (these would only cost the bank money in central bank surcharges unless they were put to work in fee-earning products).

Ermotti made clear he was fully «risk-off» by late 2017, telling telling «Bloomberg» that it was «the only thing you are paranoid about» if you are CEO of a bank. He would rather swallow the opportunity cost than take the risk, the erstwhile trader said.

This also marked the beginning of Ermotti’s most tiresome chapter, marked by major C-suite ructions and an organizational move that baffled some investors. By 2018, Zeltner was out after UBS elected to merge its flagship wealth unit and a U.S.-based brokerage.

Mystifying People Moves

The move failed to mask the lack of growth and impetus from the unit, which finews.com reported (click here and here to read more). Later the same year, Ermotti appears to have bumbled the exit of Andrea Orcel, a key ally and potential successor, as finews.asia reported.

He also tapped board member Axel Lehmann for management, later entrusting him with the Swiss business – mystifying, given UBS' ample in-house talent pool. Most crucially, the wealth unit effectively lost a year through management changes, after ex-Commerzbank boss Martin Blessing’s stint co-running the unit proved short-lived.

Meanwhile, Ermotti increasingly aired his frustration over UBS’ share price, which in 2018 careened from 19.75 Swiss francs to 11.66 francs (one year later, it had crashed through 10 francs for the first time in seven years).

No Double-Digit Lame Duck

To Ermotti's credit, he never settled for a double-digit-million-earning «lame duck» role: he poached Iqbal Khanhe poached Iqbal Khan from Credit Suisse last year, dismissed Blessing, and paved the way for a dignified exit for Koerner, his erstwhile rival for the top job. His biggest setback – a $5 billion French criminal penalty – is likely to remain a painful footnote in an otherwise stellar career.

He also showed little signs of slowing down, though he became more distant and perceptibly more sensitive to criticism. It became clear Ermotti had been planning his post-UBS career for some time when he was designated as Swiss Re's next chairman. Given Ermotti's near-total reversal on risk-taking, the reinsurance job is the crowning achievement of his 33-year career in high finance.

Smashing Hidebound Set-Up?

Ermotti's legacy is apparent in UBS' last set of results: the Swiss wealth manager is rock-solid despite the pandemic, and investors appear to finally be willing to pay a premium for the bank's boredom. Ralph Hamers, who takes over next Monday, is getting the world's largest private bank which has the tools to fight the digital battle, but whose bureaucracy makes for frequent bottlenecks, and which is weighed by the French case.

Ermotti also made little effort tackling UBS' famous hierarchy, and unlike his peer at Credit Suisse, Tidjane Thiam shied away from major job cuts in Switzerland. He leaves UBS in an excellent strategic position, but the bank needs Hamers to tackle its corporate culture to develop its full potential.