Corona's Warning Shot for Private Banks

Swiss wealth management is rapidly consolidating – a process set to accentuate to due to the pandemic. But banks are also to blame.

The coronavirus pandemic isn't genuinely a banking crisis – but Switzerland's wealth managers are being sucked in. The steady march of consolidation in recent years is about to evolve into a blast of dealmaking.

That's what Boston Consulting Group is predicting in a new study on wealth management. The BCG authors forecast that one-fourth of Switzerland's private banks will disappear by 2025.

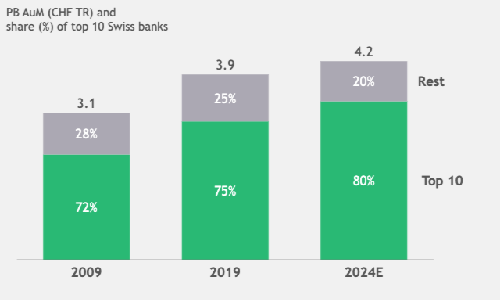

Top Ten Expands Lead

Even if BCG is less dramatic than its competitors, consolidation is nothing new in Switzerland. In 2010 the ten largest private banks held 72.5 percent of assets managed in Switzerland (click on the graph below). By last year, the sum had risen to 75 percent and is expected to rise to four-fifths of assets by 2024.

This lays bare that consolidation, spurred by the coronavirus pandemic, will accentuate. The ensuing economic crisis is melting asset piles, meaning smaller institutes on a knife-edge will be driven into the arms of their bigger rivals.

At least, those that haven't yet adapted to the new regulatory reality, or found a new business model which caters to the changing requirements of their clients after banking secrecy.

Cutting Spend Until 2018

It began well enough following 2008/09: Swiss firms slimmed down from pre-financial crisis levels. They worked at being more profitable and efficient; BCG's data illustrates that private banks lowered what they spent compared to assets to a sporting 63 basis points, from 79 points previously.

Those days are over, and 2018 marked the turning point: banks began spending a lot more. Initially, they poured money into digitization efforts, more recently funds their legal and compliance spending surged. Last year, the cost over assets metric had already edged to 64 basis points, and BCG predicts it will climb to an average of 69 points by 2024 (higher or lower depending on each banks' discipline on its pursestrings).

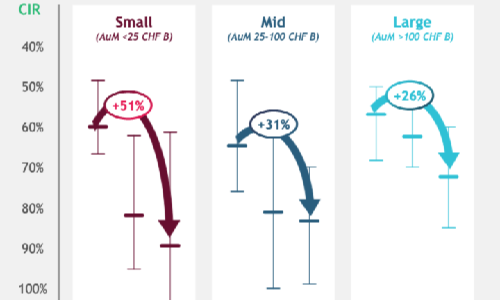

Massively Less Efficient

The more traditional spending metric is even more dramatic: smaller private banks (in BCG's worldview, those with less than $25 billion in assets) saw their cost-income ratio climb 51 percent from 2007 through last year (click on graph below).

Larger firms – those with more than $100 billion – have it easier: their cost-income ratios also rose on average, though «only» by 26 percent. Roughly one-third of all private banks are in trouble with the metric, which cost-income ratios of over 90 percent.

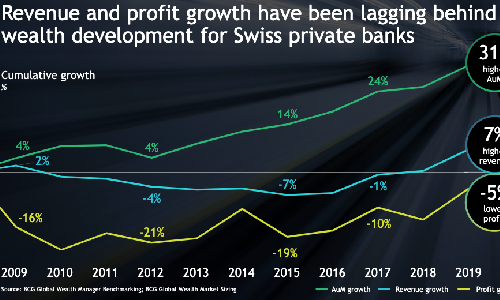

Assets Rise, Profits Tank

The frustration for wealth managers is that assets weren't to blame for spending outstripping revenue. BCG's analysis shows (click on graph below) that assets under management actually rose by 31 percent in the last ten years.

Unfortunately, revenue only grew by a mild seven percent in the same period – and profit shrank by five percent. This came against the backdrop of the longest bull market in history with average asset growth globally of 6.2 percent (in Switzerland, seven percent last year).

Shot Across The Bow

This shows that banks need to get fitter and more profitable if they want to survive. What use are rising revenues if firms are turning around and spending nine-tenths?

Not all wealth managers will survive the leap, BCG predicts. The consulting firm forecasts a dramatic accentuation of mergers-and-acquisitions in the sector in the coming years; small, unprofitable, and shiftless banks are most at risk. The coronavirus pandemic is a shot across the bow for private banks to return to the activism they showed following the last major crisis.