Everything is About the Private Banker in 2024

The performance of Swiss wealth managers in 2023 makes one thing very clear. They have a growth problem, as a finews.com peer comparison convincingly shows. It also means that all eyes are on front-line private bankers this year.

There is a certain irony in the current situation. Last year was one in which the country's two leading financial institutions, UBS and Credit Suisse, became one. The step was supposed to create an avowed wealth management powerhouse. Instead, what happened was that most players in the industry were left relatively empty-handed.

Swiss and Liechtenstein institutes complained about a toxic mix of Swiss franc strength, turbulent equity markets, and general client restraint. The sharp rise in interest rates also weighed heavily, given that high-net-worth private clients took money out of riskier, more lucrative, high-margin products and put them in cash or money markets instead. They also kept away from relatively high-interest Lombard loans and other collateralized lending products, something that in previous years tended to pad out overall industry profitability rates.

Stagnating Volumes

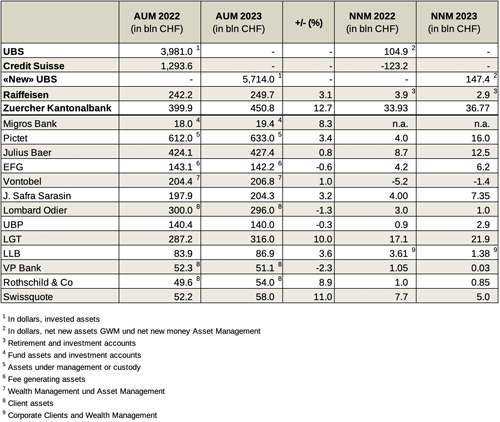

Those factors impacted both wealth and asset management businesses, the two pillars that most specialized Swiss banking houses depend on. Our comparison shows that only a few saw double-digit volume increases, with a few even reporting outright declines.

Renowned institutions such as EFG International, Lombard Odier, and UBP had fewer assets on their books at the end of 2023 than they did a year earlier, the finews.com chart shows (image below). It is not a ranking per se, but a specific selection of the leading 11 Swiss institutions given several large Geneva-based institutions do not provide numbers publicly, with the picture being additionally fleshed out by the major banks and large domestic retail and corporate banking franchises. Naturally, comparison figures for the new UBS-CS entity are missing.

Newly Defined

The numbers rely on a relatively wide definition of client assets because of the differences in how assets under management are quantified at each. That includes UBS's new determination of net new assets from the third quarter, something it believes makes its figures more comparable with US peers than the more domestically recognized net new money metric does.

The assets figure includes interest receipts and dividends on invested assets, which usually leads to higher reported numbers for its Wall Street brethren.

No Stable Pillar

Despite all that, UBS's results were seen as coming in below expectations by certain market observers, something that prompted criticism of the Global Wealth Management (GWM) business led by the indefatigable, even restive, Iqbal Khan. But the voices are not just blindly poking about in the dark. The wealth management franchise is where the promise of becoming a global powerhouse will be kept - or broken. By 2028, UBS is targeting the $5 trillion mark in invested assets. To do that, it has to grow new assets by $200 billion a year from 2026 onwards.

The net new money results of its main peers were not stable pillars to rely on either. Instead, most saw them fluctuate wildly. Geneva's Pictet reasonable growth was contrasted by a decline in the likes of EFG, with Liechtenstein's VP Bank and investment house Vontobel showing relatively hefty declines, the latter mostly because of the asset management business. Solid growth rates such as those reported by LGT and the Zurich Cantonal Bank were more the exception than the rule.

Dreams and Reality

That means two things. First, the difficult new money conundrum that the industry has been confronted with for years is still a reality in the post-pandemic era. Moreover, Credit Suisse's collapse has not resulted in massive outflows to other institutions. This is the case even though many players such as Lombard Odier, EFG, and Julius Baer have been hiring large numbers of Credit Suisse bankers - at high expense.

That now puts them under concentrated pressure given the ambitious growth plans they all have. By 2030, Julius Baer wants to be managing about $1 trillion in assets while the likes of an EFG already expects to be attracting $10 billion in net new money annually, something it was very far from achieving in 2023.

Perfect Conditions

Nobody is interested in the distraction of a large takeover right now given the continued profitability of the industry as a whole and the higher interest rate environment. That means they have to rely on organic growth as the only realistic way to achieve their avowed targets and the only hope to do that is to hire reams of front-line bankers able to attract new assets.

It also creates the perfect environment for private bankers as their importance to each and every bank can't be overstated. Given that, they can expect to see a continued job market with plenty of opportunities and ample pay packages as they hope from one institution to another. Those who stay won't be far worse off either. Rainmakers are likely to be in a position to reap high bonuses, as recent media reports involving Julius Baer indicate.

Two More Years

On the other hand, certain bankers will face increasing pressure to perform after they join a new institution. Normally, they get two to three years to convince their clients to move with them before patience wears thin with management.

Still, given the current difficult market for new assets in the industry, most of the recruits will probably be working somewhere else by the time 2026 rolls in.